CHAPTER 2

Louise Norton-Varèse, Edgard Varèse, Suzanne Duchamp, Jean Crotti, und Mary Reynolds (left to right), 1924

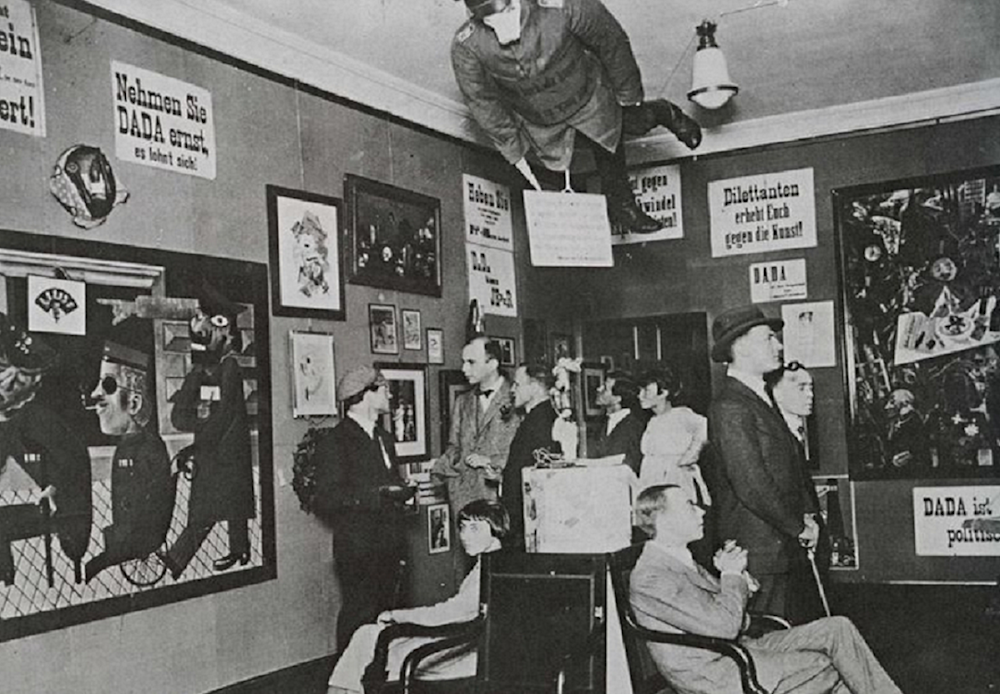

The artist’s pub «Cabaret Voltaire», 1916

Man Ray, portrait of Tristan Tzara, ca. 1921

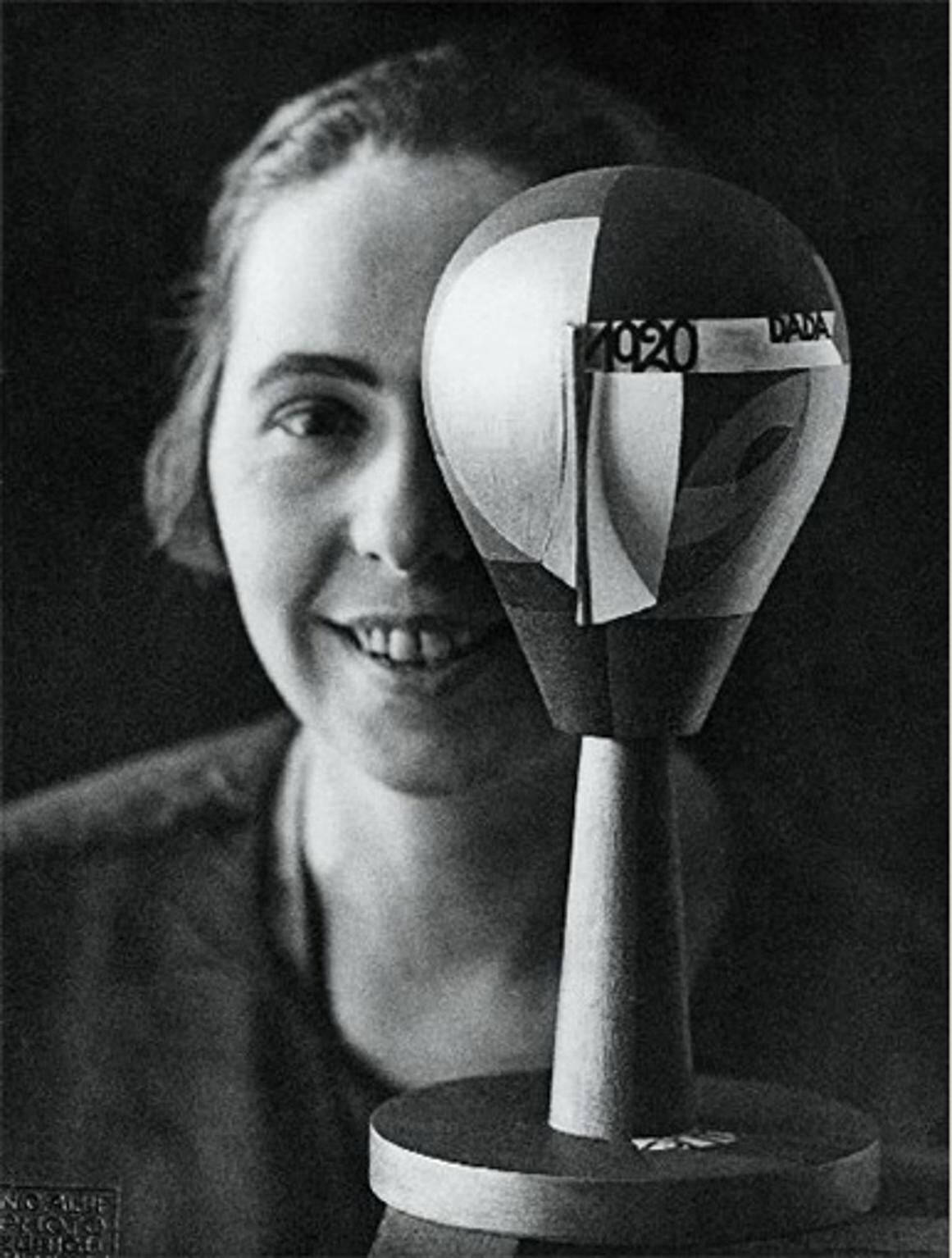

Nic Aluf, portrait of Sophie Taeuber-Arp with «Dada-head», 1920

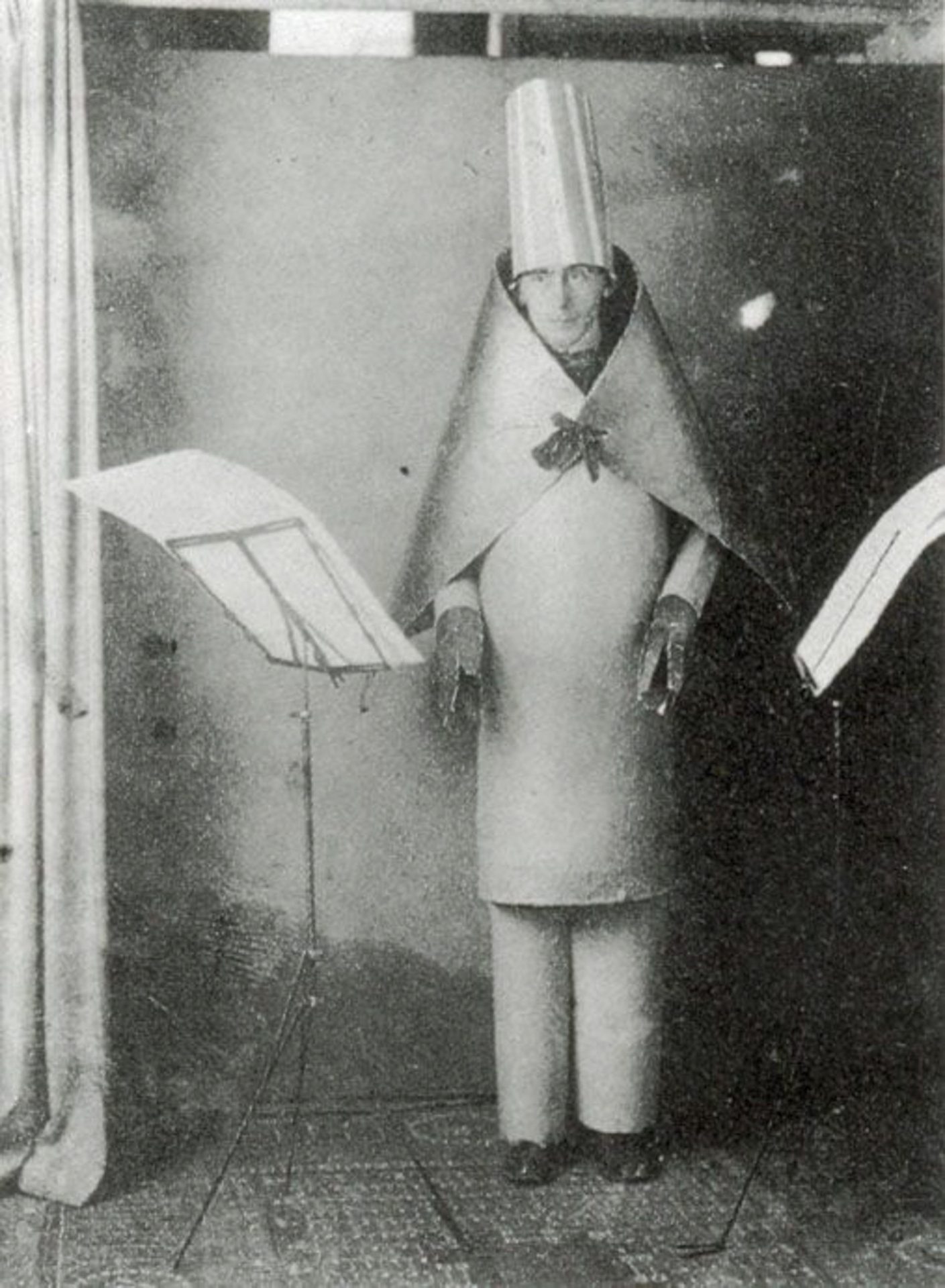

Hugo Ball performing his «Verse without Words», 1916

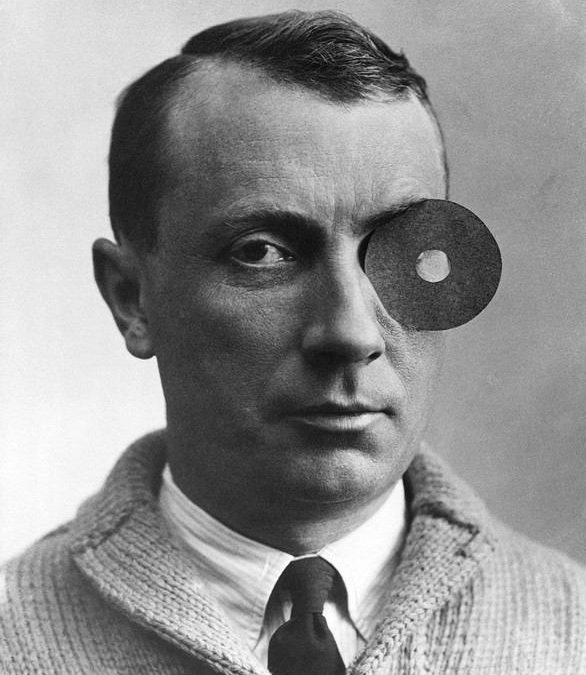

Hans Arp, Self portrait with «Navel-monocle», 1926

Hannah Höch with Dada dolls, 1925

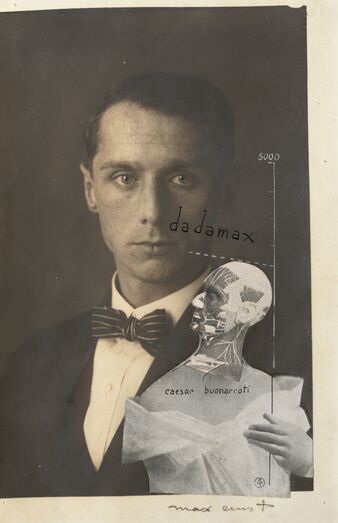

Max Ernst, Le Punching Ball ou l’immortalité de Buonarroti (The Punchingball or the immortality of Buonarroti), 1920

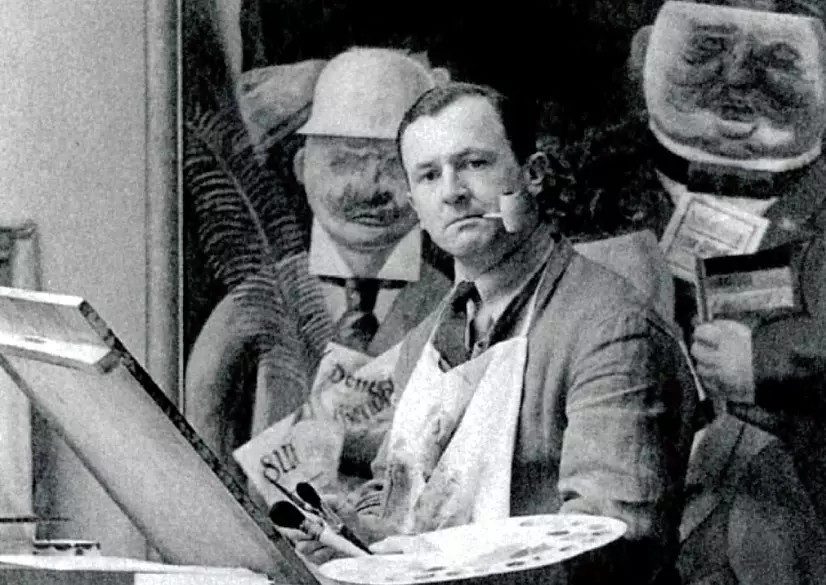

George Grosz in his atelier in Berlin in front of his painting «Stützen der Gesellschaft» (Pillars of Society), 1926

John Heartfield, Self-portrait, 1920

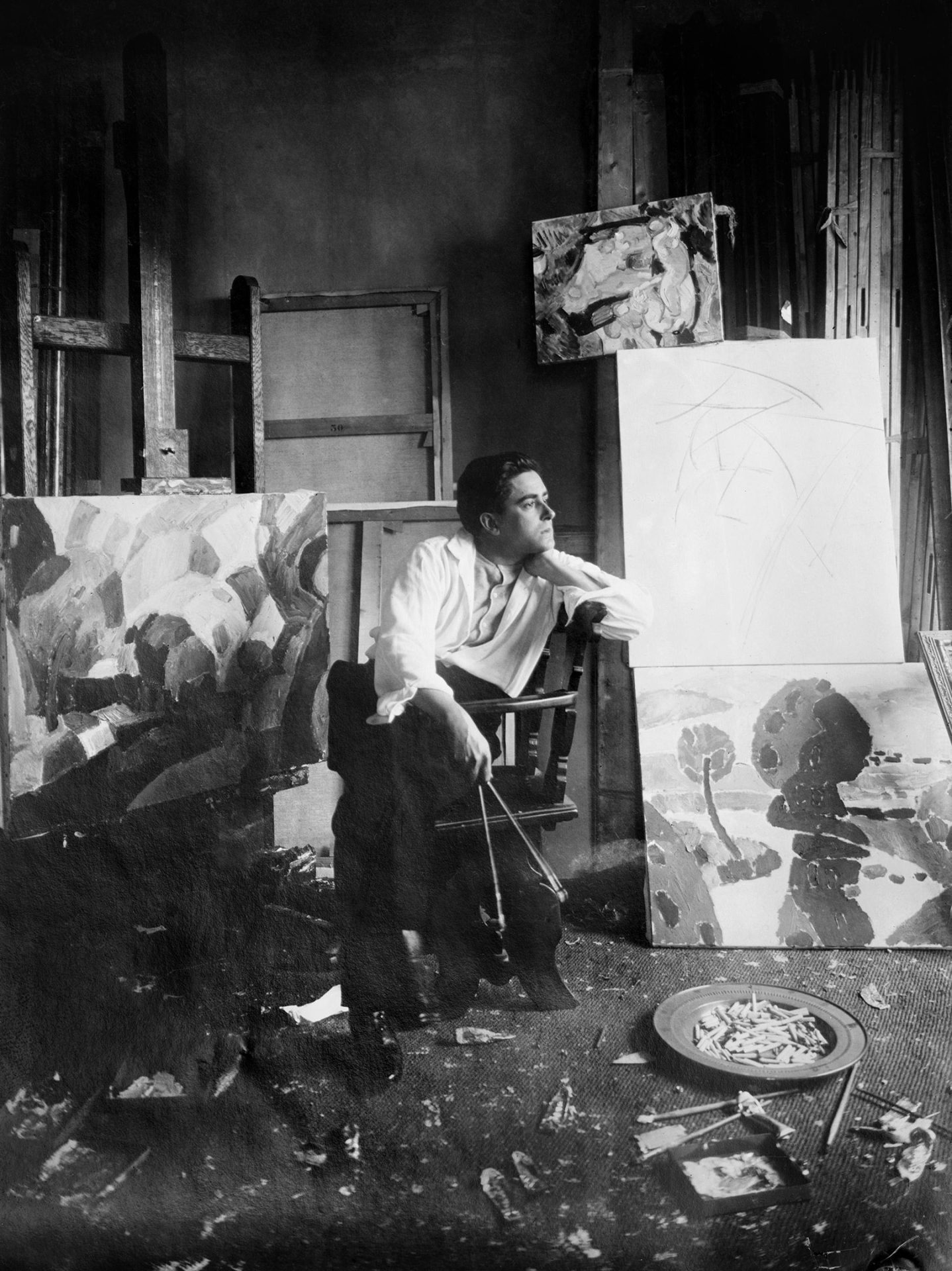

Paul Thompson, Jean Crotti in his New York studio, ca. 1915

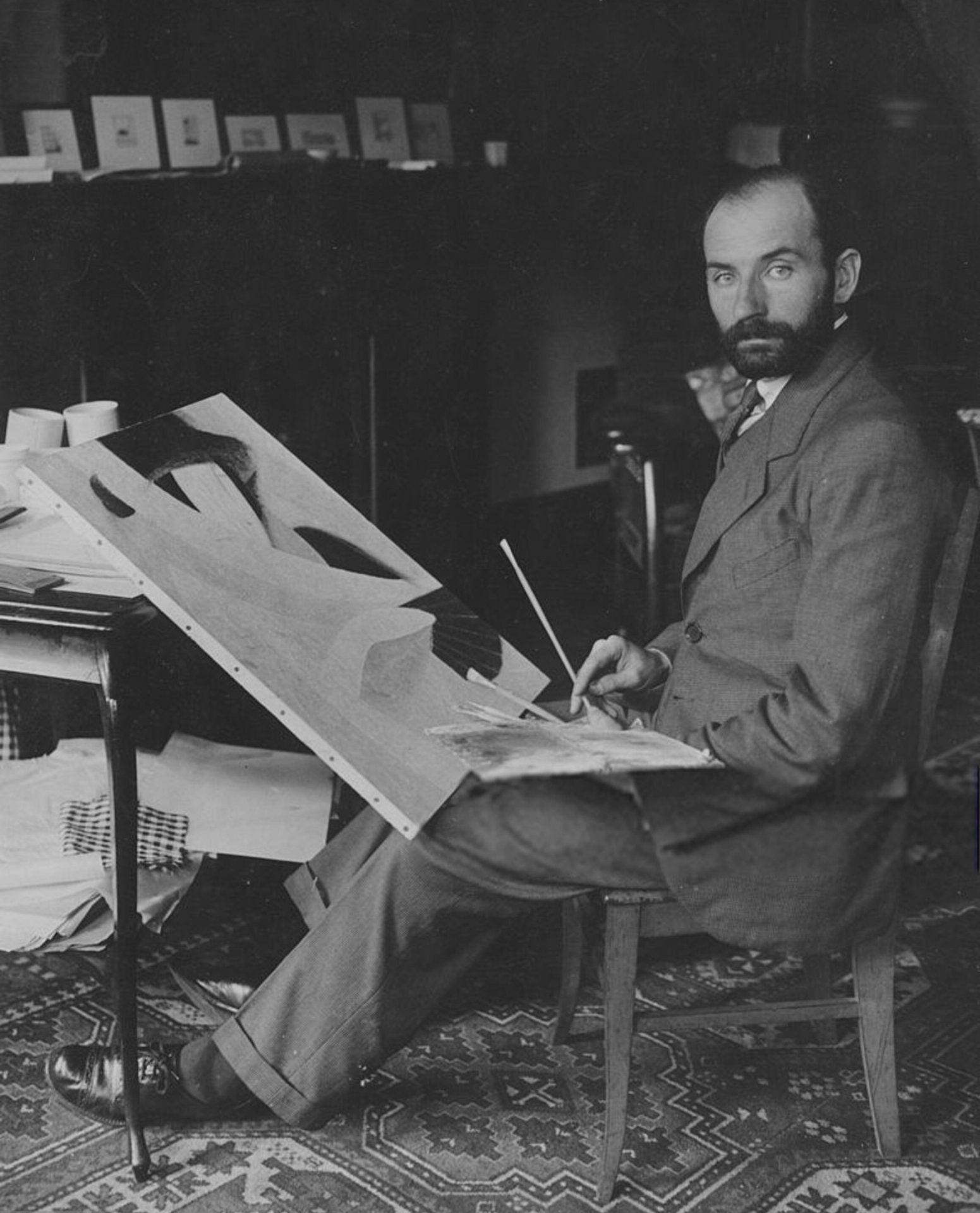

Francis Picabia in his studio in New York City, ca. 1915

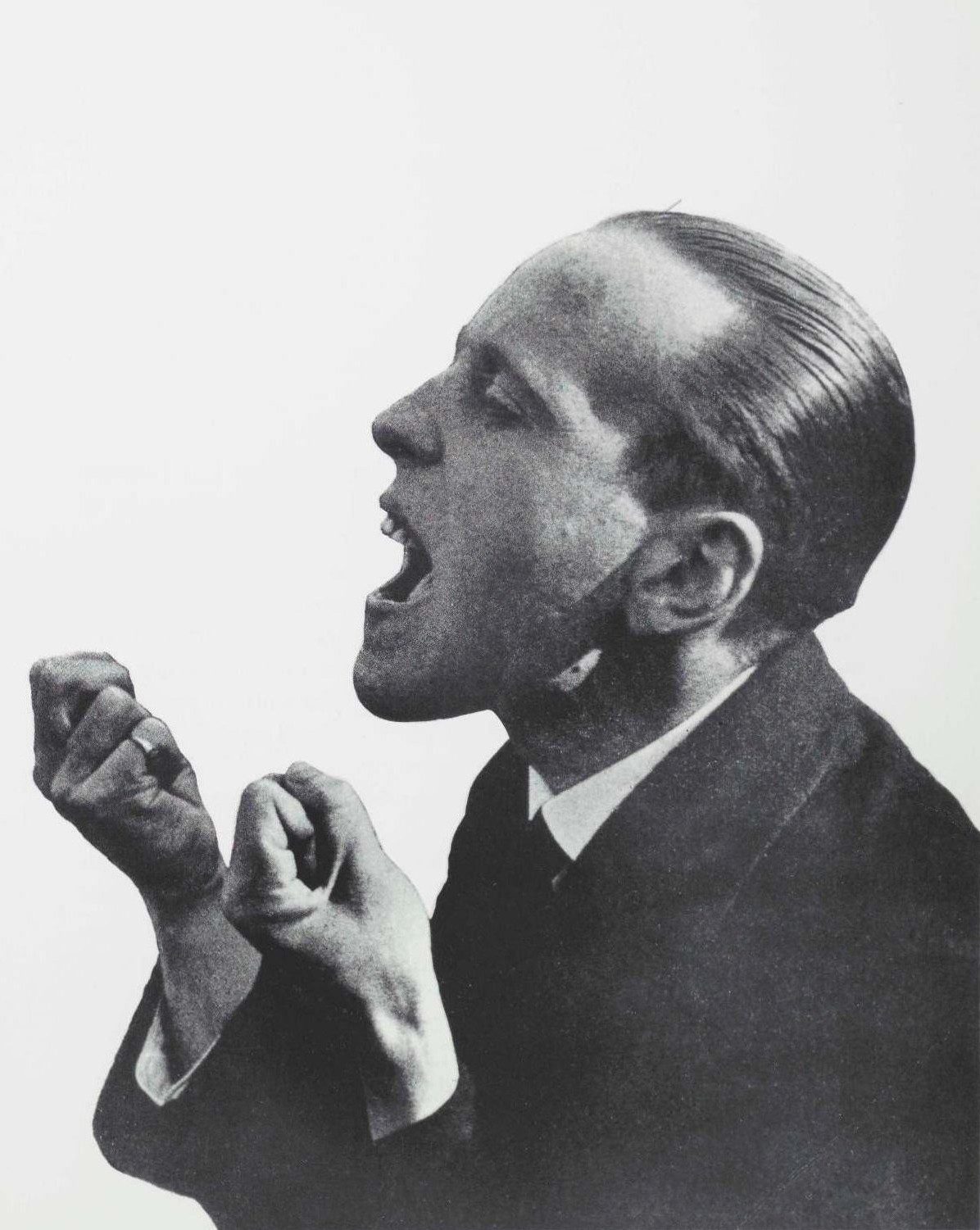

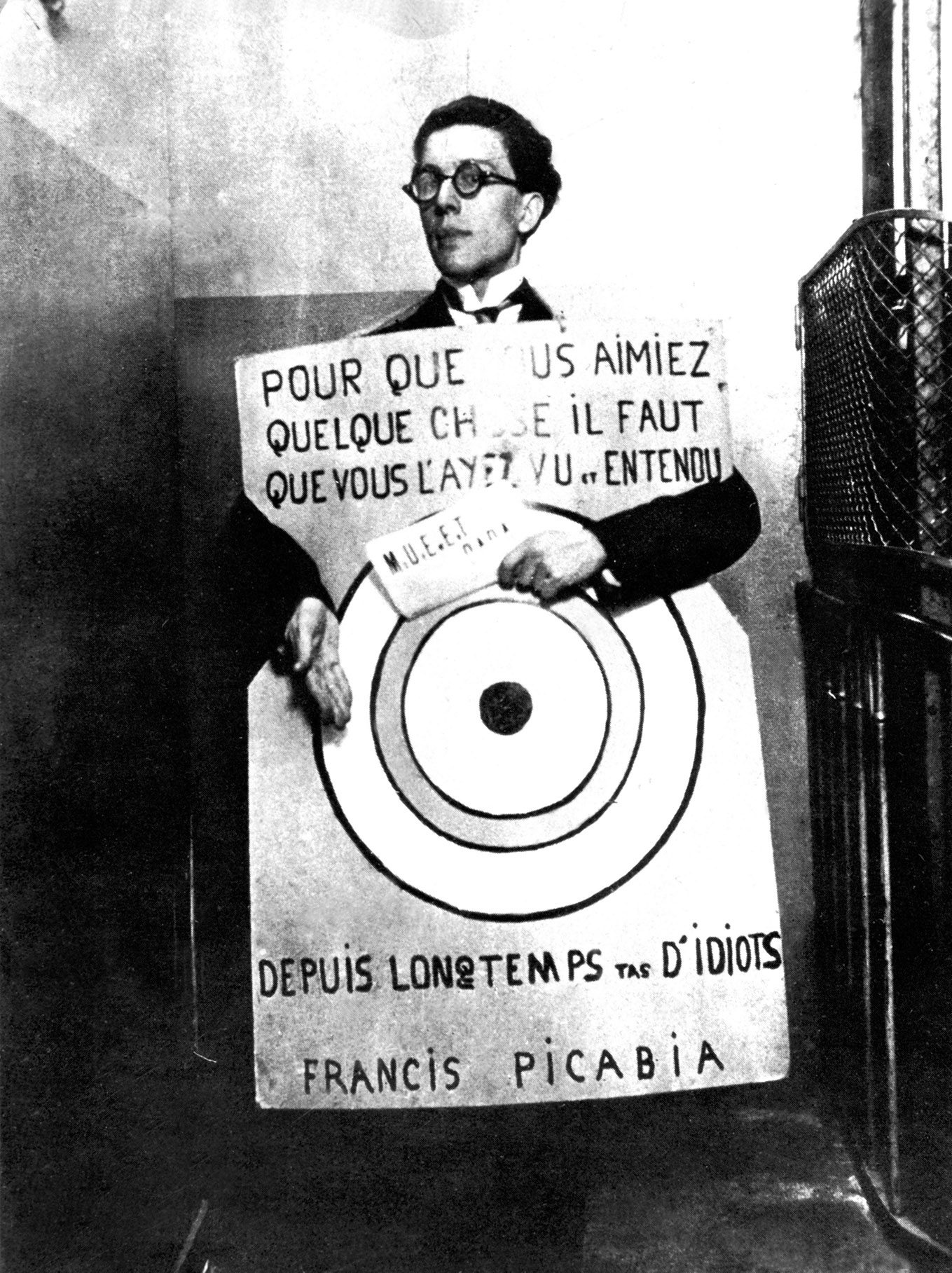

André Breton at «Festival Dada» in the Theatre de l’Oeuvre in Paris, 1920

Sonia Delaunay-Terk in Delaunay‘s apartment on Boulevard Malesherbes, Paris, 1924

Marcel Duchamp, Portrait multiple de Marcel Duchamp (Multiple-portrait of Marcel Duchamp), 1917

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven dancing, ca. 1922

Beatrice Wood (on the right) with Marcel Duchamp (on the left) and Francis Picabia (center), 1920s

Charles Fraser, Man Ray with Photokina-Eye, 1960

A photograph of Marcel Duchamp from his portable ‹miniature museum›, known as «La boîte en valise» (Bos in a Suitcase), and a painting after the photograph by Suzanne Duchamp show one of their first joint readymades. After Suzanne Duchamp and Jean Crotti married in Paris on April 14, 1919, Marcel Duchamp sent them as a wedding present instructions as to how they should execute the readymade. Later he said of the collaborative work: «It was a book on geometry, which he (Crotti) was to hang up by a thread on the balcony of his apartment in rue Condamine; the wind was to blow the book and choose its own problems, turn the pages and rip them out.»

Suzanne Duchamp, Le readymade malheureux de Marcel, 1920

Marcel Duchamp, Le readymade malheureux (The unhappy readymade) from La boîte en valise (Box in a Suitcase), 1959